This article first appeared on the author’s Planetary Vegan website on 15th March 2018.

Paul Hawken is an American journalist, author and activist. He recently visited my home country, Australia, to speak about “Project Drawdown“, of which he is the executive director.

The project’s mission is “facilitating a broad coalition of researchers, scientists, graduate students, PhDs, post-docs, policy makers, business leaders and activists to assemble and present the best available information on climate solutions in order to describe their beneficial financial, social and environmental impact over the next thirty years.”

The results of the project were documented in the 2017 book “Drawdown: The most comprehensive plan ever proposed to reverse global warming”, which was edited by Hawken.

Eighty of the one hundred solutions were said to be “well entrenched with abundant scientific and financial information about their performance and cost”. The other twenty were described as “coming attractions” that are “forthcoming and close at hand”.

In what may be something of a contradiction, all one hundred were also described as the “most substantive, existing solutions to address climate change”.

From an initial review of Drawdown’s findings, I feel there are some aspects worth highlighting, some of which are a cause for concern.

The project focuses on more than drawdown

In relation to climate change, the term “drawdown” generally indicates the act of drawing carbon from the atmosphere. Project Drawdown combines that approach with the aim of avoiding future emissions. Although it is wise to consider each approach, the inclusion of the latter may cause the project’s title to be something of a misnomer.

Plant-rich diet

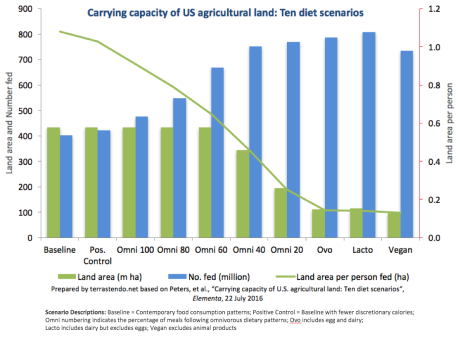

The researchers ranked a plant-rich diet fourth behind refrigeration, wind turbines and reduced food waste. I was pleased they had investigated the impact of diet, as it is a critical issue that has been ignored by many individuals and organisations campaigning on climate change. However, for various reasons, this solution could have been ranked higher, with a greater impact than indicated in the report.

One of those reasons is referred to in the next item, dealing with the global warming potential of different greenhouse gases.

Another is the fact that the authors of this chapter appear to have ignored the ability of native vegetation to regenerate if production animals are removed from areas that are currently used for animal agriculture.

That contrasts with the chapter on regenerative agriculture, where the authors noted that, apart from deserts and sand dunes, bare land will naturally revegetate.

The chapter on afforestation only considered the option of planting trees, and solely in areas that had been treeless for at least fifty years.

Some examples help to illustrate the importance of this issue:

- A 2009 study by the PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency indicated that a global transition to a meat-free or animal-free diet would reduce climate change mitigation costs by 70-80 per cent. A key factor would be the ability of lands cleared or degraded for livestock grazing and feed crop production to regenerate forests and other forms of vegetation.

x - Eastern Australia has been included by WWF in a list of eleven global deforestation fronts to the year 2030 due to concerns over land clearing legislation in Queensland and New South Wales. Two-thirds of clearing in Queensland in the four years to 2015/16 (the most recent reporting period) was of regrowth, indicating the resilience of native vegetation if given an opportunity to recover.

x - Researchers behind a 2005 paper published in Nature estimated that massive portions of the north and south Guinea Savanna in Africa would have a reasonable chance of reverting to forest if livestock were removed. Their status as savanna is anthropogenic.

In addition to the issue of regrowth, two near-term climate forcers, tropospheric ozone and black carbon, are unlikely to have been accounted for in the life cycle assessments utilised by the Drawdown researchers. They are also generally omitted from official emissions figures, but are prominent in animal agriculture. They remain in the atmosphere for a short period, but have a significant impact.

Loss of soil carbon from grazing and livestock-related land clearing may also have been overlooked.

Allowing for tropospheric ozone, loss of soil carbon resulting from livestock-related land clearing, a 20-year global warming potential (refer below) and other factors, researchers from the Sustainable Society Institute at the University of Melbourne and climate change advocacy group Beyond Zero Emissions (BZE) have estimated that the livestock sector is responsible for around fifty per cent of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions. The findings were reinforced in a subsequent peer-reviewed journal article, which had two co-authors in common with the BZE paper. The figure compares to the official figure of around ten per cent, as referred to by the Drawdown authors.

The warming impact of greenhouse gases

A shorter time horizon for measuring the global warming potential (GWP) of the various greenhouse gases should have been considered in addition to the more common 100-year period (GWP100).

A commonly cited alternative period is 20 years (GWP20), with the IPCC and NASA providing relevant estimates. The GWP20 for methane is 86 times that of carbon dioxide after allowing for climate carbon feedbacks. Allowing for aerosol interactions, NASA researchers have estimated a multiple of 105.

The issue is critical in the context of climate change tipping points and feedback mechanisms with the potential to lead to runaway climate change over which (by definition) we would have no control.

A shorter time horizon would seem particularly relevant given the project’s focus on the next thirty years, and would have increased the impact of three of the top four solutions, namely refrigeration, food waste and a plant-rich diet.

Managed grazing

All Drawdown’s solutions are said to be “based on meticulous research by leading scientists and policymakers around the world”.

But how meticulous was the research?

The standard may have been lowered for the 19th-ranked solution, managed grazing, which is said to include techniques such as “improved continuous”, “rotational”, “adaptive multipaddock”, “intensive” and “mob” grazing.

Using similar terms, including “rotational” and “mob” plus “regenerative”, “cell”, “adaptive” and “management-intensive rotational”, researchers at the Food Climate Research Network (FCRN) argued in 2017 that the “extremely ambitious claims” made by proponents of regenerative grazing and associated approaches are “dangerously misleading”.

FCRN is based at the University of Oxford. Other institutions that contributed to the relevant publication comprised: Universities of Aberdeen, Cambridge and Wageningen; the Centre for Organic Food and Farming (EPOK) at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU); the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) in Switzerland; and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australia.

Although Drawdown credits the initial investigation of managed grazing to Frenchman André Voison in the 1950s, its description of the techniques appears to align with the work of Allan Savory and the Savory Institute. Drawdown states, “managed grazing imitates what migratory herds of herbivores do on wildlands”. Savory argues we must “use livestock, bunched and moving, as a proxy for former herds and predators, and mimic nature“.

Hawken, Amory Lovins and Hunter Lovins wrote favourably about Savory’s methods in their 1999 book “Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution”. Hunter Lovins is a member of the Savory Institute’s “Advisory Circle”, and defended Savory’s methods in a response to a critique of his work by Guardian columnist, George Monbiot. Hawken has also praised Savory’s work individually.

Two other Savory supporters, Bill McKibben (co-founder of 350.org) and Adam Sacks, are advisors to Project Drawdown. Sacks and another Savory Institute “Advisory Circle” member, Seth Itzkan, have taken credit for influencing McKibben in his support of Savory’s methods.

In prominent 2010 articles supporting Savory’s methods, McKibben and Sacks appear to have erroneously relied, in part, on what McKibben referred to as “preliminary research” favourable to livestock grazing. Critical measurements within that research were subsequently found to be out by a factor of 1,000. The articles from McKibben and Sacks have never been corrected. (I comment on them in item 2.2 here.)

Similar problems in relation to the same preliminary research have occurred in the work of Australian soils ecologist, Christine Jones, who has been cited by Sacks and others who promote Savory’s methods.

Errors can be difficult to avoid, and in this case the original research was corrected. However, the matter does not appear to have been adequately addressed in the material from McKibben, Sacks and Jones, referred to here, that utlilised it.

The FCRN authors cited a review by Swedish researcher Maria Nordborg, who analysed evidence put forward by the Savory Institute. She found the studies supporting Savory to be scanty, “generally anecdotal” and “based on surveys and testimonies rather than on-site measurements”.

Similarly, a 2014 article published in the International Journal of Biodiversity examined each of Savory’s claims. The authors stated that studies supporting Savory’s methods: “have generally come from the Savory Institute or anecdotal accounts of holistic management practitioners. Leading range scientists have refuted the system and indicated that its adoption by land management agencies is based on these anecdotes and unproven principles rather than scientific evidence.”

Drawdown appears to push aside scientific rigour in defending managed grazing practices. It does so, in part, by arguing that the transition period from traditional grazing to alternative approaches is two to three years, “about the same length of time as most of the studies that question the results shown by proponents”.

It is disappointing that a book which is claimed to be based on meticulous research argues that peer-reviewed papers criticising managed grazing practices are invalid because they are assumed to only cover the period of transition from one system to another. That is not meticulous work by the Drawdown team; it is subjective and extremely questionable.

The managed grazing issue seems almost a central theme for the authors. In addition to the chapter specifically focusing on the issue, it is mentioned in the foreword by Tom Steyer (using the term “regenerative grazing”) and in the chapters headed Plant-Rich Diet; Regenerative Agriculture; and A Cow Walks onto a Beach.

Although managed grazing may be viable on a relatively small scale subject to adequate water resources and livestock controls, it would never be sufficient to feed the masses. Animal-based food production is a grossly and inherently inefficient method of satisfying our nutritional requirements, and has a far greater impact on the natural environment than animal-free options. It causes us to use far more resources, including land, than would otherwise be required.

Permafrost and the mammoth steppe

A similar approach seems to have been taken in relation to the “coming attraction” of repopulating the mammoth steppe with grazing animals, as proposed by Russian scientist Sergey Zimov.

The steppe is a massive ecosystem that once extended “from Spain to Scandinavia, across all of Europe to Eurasia and then on to the Pacific land bridge and Canada”.

It contracted nearly 12,000 years ago, around the end of the most recent ice age. Large herbivores that once grazed its extensive grasslands also largely disappeared.

Zimov argues that reintroducing grazing animals would promote grasslands and remove the supposed insulating effect of snow on permafrost due to the animals’ practice of removing it in order to access pasture. He contends these changes, along with a related restriction in wooded vegetation, would prevent the melting of permafrost, which would be critical to any efforts to overcome climate change.

Central to Zimov’s argument is the belief that the nature of the steppe’s flora changed due to hunting, which caused the extinction of large herbivores that once populated the region, keeping wooded vegetation in check and acting in favour of perennial grasslands.

The conventional view, on the other hand, is that the animals became extinct because of the warming climate, resulting in the growth of wooded vegetation at the expense of grassland.

The Drawdown authors flippantly disregard conventional “published papers” that have been unable to “taint” Zimov’s excursions in the mammoth steppe. Do those papers count for nothing in a project based on “meticulous research”?

A major concern with Drawdown on this issue is the sheer scale of the permafrost problem.

Permafrost is soil, sediment or rock that remains at or below 0°C for at least two years. It covers around twenty-four per cent of exposed land in the northern hemisphere and extends to offshore Arctic continental shelves. It ranges in thickness from less than 1 metre to more than a kilometre.

The Earth’s atmosphere contains about 850 gigatons of carbon. Researchers at the National Snow and Ice Data Center estimate that there are about 1,400 gigatons of carbon frozen in permafrost. Figure 1 illustrates the extent of permafrost in the northern hemisphere.

Figure 1: Permafrost map. Darker shades of purple indicate higher percentages of permanently frozen ground.

With rising temperatures, the permafrost has begun to thaw, releasing methane and carbon dioxide from decomposing organic matter within.

The release of those greenhouse gases creates a significant climate feedback mechanism, as it causes more warming, resulting in more thawing, then more warming, and so on.

The Drawdown authors seek to add perspective to the potential impact of Zimov’s attempt to preserve permafrost by stating: “If it came to pass, it would be the single largest solution or potential solution of the one hundred described in this book.”

But could Zimov’s efforts, if we were to assume his theory was sound, put even a dent in the permafrost problem?

In 2011, the Russian head of the International Arctic Research Centre at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Igor Semiletov, was astonished by the extent of methane being released from permafrost in the seabed of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf. He said:

“We carried out checks at about 115 stationary points and discovered methane fields of a fantastic scale – I think on a scale not seen before. Some of the plumes were a kilometre or more wide and the emissions went directly into the atmosphere – the concentration was a hundred times higher than normal.”

Five years later, Dr Semiletov reported:

“The area of spread of methane mega-emissions has significantly increased in comparison with the data obtained in the period from 2011 to 2014. These observations may indicate that the rate of degradation of underwater permafrost has increased.”

Quite apart from the massive scale of the permafrost problem, would not the methane emissions from a growing population of ruminant animals such as bison, oxen and reindeer be a concern?

Seaweed and methane

In a chapter with the title “A cow walks onto a beach”, the authors highlight the ability of a livestock feed supplement containing the seaweed species, Asparagopsis taxiformis, to reduce methane emissions.

A key difficulty with this potential solution would be its application, which may be limited to dairy and feedlot animals, where the inclusion of dietary supplements is a straightforward process.

The emissions intensity of dairy products and beef from feedlot cattle and the dairy herd is already extremely low compared to that of specialised beef from grazing animals, meaning that the relative benefits of the supplement may be smaller than initially assumed.

Some more research that is far from meticulous

Some more examples of material that is inconsistent with Drawdown’s claims of scientific rigour and meticulous research may be worth mentioning.

Percentage of land surface

In the section on silvopasture, the authors claim that cattle and other ruminants require 30 to 45 per cent of the world’s arable land (my underline). However, the cited sources based their figures on the world’s total land surface, not just arable land.

At the time of writing, the name of one of the editors, Veerasamy Sejian, had been omitted from the relevant source on the Drawdown website.

Gigaton volume

In a section on numbers, the authors seek to demonstrate the volume of a gigaton of carbon dioxide. However, they use the volume of a gigaton of water, which represents a small fraction of a gigaton of carbon dioxide’s volume.

To illustrate the dimensions, they use 2016’s emissions of 36 gigatons of carbon dioxide, indicating they would equate to around 14 million Olympic-sized pools. That is based on the fact that one tonne of water occupies one cubic metre.

However, one tonne of carbon dioxide occupies not 1 cubic metre, but 534.8! That is 8.12 x 8.12 x 8.12 metres, not 1 x 1 x 1.

Figure 2: Volume of one tonne of carbon dioxide

That means that 36 gigatons of carbon dioxide equates to around 7.7 billion Olympic-sized pools, not 14 million.

1.5°C vs 2°C

In their comments on the mammoth steppe (referred to earlier in this article), the Drawdown authors paint a clear line between the impacts on permafrost of temperature increases of 1.5°C and 2°C. In reality, there is no distinct line between the two.

They suggest that, beyond 2°C, “the emissions released from the permafrost will become a positive-feedback loop that accelerates global warming”. However, that is already happening; it is simply a question as to how strongly the feedback mechanism operates at different temperatures.

Carbon dioxide vs methane

Also in the section on the mammoth steppe, the authors refer to the release of “carbon and methane” to the atmosphere.

It is important to note that both carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) contain carbon atoms. The authors may have meant “carbon dioxide and methane” but their intention is unclear.

Where did the nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide go?

In the chapter on seaweed and methane (“A cow walks onto a beach”), the authors correctly point out that methane emissions from enteric fermentation in the digestive system of ruminant production animals represent around 39 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions from livestock production.

They then mention that methane is not the only greenhouse gas caused by livestock, but fail to mention the others. They simply indicate that feed production and processing accounts for around 45 per cent of livestock-related emissions. Those emissions are split fairly evenly between carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide.

Using the authors’ source document (from the UN FAO) the split is: methane 43.8% (including manure management and rice used as animal feed); nitrous oxide 29.3%; and carbon dioxide 26.9%.

Those apportionments are based on a 100-year global warming potential for measuring the relative impact of the various greenhouse gases. Based on a 20-year GWP, methane’s share increases to 66 per cent.

Animal suffering, human health, and more on climate change

The Drawdown authors appear to have fallen for the trap of assuming that animal agriculture outside the regime of factory farming has little negative impact on animals, human health and the climate. For example, they claim that there are “reams of data” regarding the contribution to climate change of conventional cattle raising systems that involve feedlots. But where is the data indicating such systems are worse than alternative forms of animal agriculture?

To the contrary, researchers from the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service, Texas A&M University and Australia’s CSIRO have reported that ruminant animals eating grass produce methane at four times the rate of those eating grain. [Footnote]

Similarly, Professor Gidon Eshel of Bard College, New York and formerly of the Department of the Geophysical Sciences, University of Chicago, has reported, “since grazing animals eat mostly cellulose-rich roughage while their feedlot counterparts eat mostly simple sugars whose digestion requires no rumination, the grazing animals emit two to four times as much methane”.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has estimated that specialised beef from grazing animals is around 6.4 times as emissions intensive as that from animals partially reared in feedlots (95.1 kg CO2-e/kg product vs 14.8 CO2-e/kg product).

In terms of human health, an April 2016 study by researchers from the University of Oxford estimated that if the global population were to adopt a vegetarian diet, 7.3 million lives per year would be saved by 2050. If a vegan diet were adopted, the figure would be 8.1 million. More than half the avoided deaths would result from reduced red meat consumption.

The results primarily reflect anticipated reductions in the rate of coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, and type 2 diabetes. They apply to all forms of red meat, and are consistent with findings of the World Health Organization, the World Cancer Research Fund and researchers from Harvard Medical School, Harvard School of Public Health, the German Institute of Human Nutrition, and elsewhere.

Alternative farming systems are not generally cruelty free. For examples, most jurisdictions permit horrendously cruel practices through exemptions to prevention of cruelty legislation in favour of the livestock sector. In terms of cattle, permitted practices generally include (without pain prevention or relief): castration; dehorning; disbudding; hot iron branding; and forced breeding, often involving artificial insemination. Such breeding practices cause the animals to be sexually violated, and may be considered illegal outside the food production system.

Conclusion

The Project Drawdown concept has much merit, but its excessive support for animal agriculture appears to conflict with its stated aims. For many who are following it in the hope of finding solutions to the climate crisis, the project may help to justify existing dietary patterns. However, a general transition away from animal agriculture is necessary, and should not be too high a price to pay in exchange for retaining a habitable planet.

Author

Footnote

Although the CSIRO subsequently reported a reduction of around 30 per cent in emissions from the northern Australian cattle herd, emissions from grass-fed cattle remain on a different paradigm to those of most food-based emissions.

References

Hawken, P (Editor), “Drawdown: The most comprehensive plan ever proposed to reverse global warming”, 2017, Penguin, http://www.drawdown.org/

Stehfest, E, Bouwman, L, van Vuuren, DP, den Elzen, MGJ, Eickhout, B and Kabat, P, “Climate benefits of changing diet” Climatic Change, Volume 95, Numbers 1-2 (2009), 83-102, DOI: 10.1007/s10584-008-9534-6 (Also http://www.springerlink.com/content/053gx71816jq2648/)

World Wide Fund for Nature (World Wildlife Fund), “WWF Living Forests Report”, Chapter 5 and Chapter 5 Executive Summary, http://d2ouvy59p0dg6k.cloudfront.net/downloads/lfr_chapter_5_executive_summary_final.pdf; http://d2ouvy59p0dg6k.cloudfront.net/downloads/living_forests_report_chapter_5_1.pdf

Queensland Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation. 2016. Land cover change in Queensland 2014–15: a Statewide Landcover and Trees Study (SLATS) report. DSITI, Brisbane

Sankaran, M; Hanan, N.P.; Scholes, R.J.; Ratnam, J; Augustine, D.J.; Cade, B.S.; Gignoux, J; Higgins, S.I.; Le Roux, X; Ludwig, F; Ardo, J.; Banyikwa, F; Bronn, A; Bucini, G; Caylor, K.K.; Coughenour, M.B.; Diouf, A; Ekaya, W; Feral, C.J.; February, E.C.; Frost, P.G.H.; Hiernaux, P; Hrabar, H; Metzger, K.L.; Prins, H.H.T.; Ringrose, S; Sea, W; Tews, J; Worden, J; & Zambatis, N., “Determinants of woody cover in African savannas”, Nature 438, 846-849 (8 December 2005), cited in Russell, G. “Burning the biosphere, boverty blues (Part 2)”, 4 Feb, 2010

World Preservation Foundation, “Reducing Shorter-Lived Climate Forcers through Dietary Change: Our best chance for preserving global food security and protecting nations vulnerable to climate change” (undated)

Longmire, A., Taylor, C., Wedderburn-Bisshop, G., “Zero Carbon Australia – Land Use: Agriculture and Forestry – Discussion Paper”, Beyond Zero Emissions and Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute of The University of Melbourne, October, 2014, http://bze.org.au/landuse

Wedderburn-Bisshop, G., Longmire, A., Rickards, L., “Neglected Transformational Responses: Implications of Excluding Short Lived Emissions and Near Term Projections in Greenhouse Gas Accounting”, International Journal of Climate Change: Impacts and Responses, Volume 7, Issue 3, September 2015, pp.11-27. Article: Print (Spiral Bound). Published Online: August 17, 2015, http://ijc.cgpublisher.com/product/pub.185/prod.269

Myhre, G., D. Shindell, F.-M. Bréon, W. Collins, J. Fuglestvedt, J. Huang, D. Koch, J.-F. Lamarque, D. Lee, B. Mendoza, T. Nakajima, A. Robock, G. Stephens, T. Takemura and H. Zhang, 2013: “Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group 1 to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change” , Table 8.7, p. 714 [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/

Shindell, D.T.; Faluvegi, G.; Koch, D.M.; Schmidt, G.A.; Unger, N.; Bauer, S.E. “Improved Attribution of Climate Forcing to Emissions”, Science, 30 October 2009; Vol. 326 no. 5953 pp. 716-718; DOI: 10.1126/science.1174760, http://www.sciencemag.org/content/326/5953/716.figures-only

Mahony, P., “GWP Explained”, Terrastendo, 14th June 2013 (updated 15th March 2015), https://terrastendo.net/gwp-explained/

Garnett, T., Godde, C., Muller, A., Röös, E., Smith, P., de Boer, I., zu Ermgassen, E., Herrero, M., van Middelaar, C., Schader, C., van Zanten, H. (2017), “Grazed and Confused?”, Food Climate Research Network, http://www.fcrn.org.uk/sites/default/files/project-files/fcrn_gnc_report.pdf

Hawken, P., Lovins, A., Lovins, L.H., “Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution” (1999), Little, Brown & Company

Savory Institute Update – December 2013, Promotion for Savory Institute e-book, “The Grazing Revolution”, http://archive.constantcontact.com/fs128/1109244198591/archive/1116032065746.html

Mahony, P., “Do the math: There are too many cows!”, Terrastendo, 26th July, 2013, https://terrastendo.net/2013/07/26/do-the-math-there-are-too-many-cows/

Mahony, P., “Savory and McKibben: Another postscript”, Terrastendo, 7th August, 2014, https://terrastendo.net/2014/08/07/savory-and-mckibben-another-postscript/

Mahony, P., “More on Savory, livestock and climate change”, Terrastendo, 23rd August, 2014, https://terrastendo.net/2014/08/23/more-on-savory-livestock-and-climate-change/

Russell, G., “Balancing carbon with smoke and mirrors”, Brave New Climate, 31st July 2010, https://bravenewclimate.com/2010/07/31/balancing-smoke-mirrors/, cited in Mahony, P., “Do the math: There are too many cows!”, op. cit.

Ferguson, R.S., “Methane, grazing and our credibility gap”, Liberation Ecology, 20th November 2017, http://liberationecology.org/2017/11/20/methane-grazing-and-our-credibility-gap/

Nordborg, M. (2016). Holistic Management: a critical review of Allan Savory’s grazing methods. Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences & Chalmers University. Sweden, https://www.slu.se/globalassets/ew/org/centrb/epok/dokument/holisticmanagement_review.pdf

National Snow and Ice Data Center, “State of the Cryosphere: Permafrost and frozen ground”, as at 4th April 2017, https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/sotc/permafrost.html

Schaefer, K., National Snow and Ice Data Center, “Methane and Frozen Ground”, https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/frozenground/methane.html

Connor, S, “Vast methane ‘plumes’ seen in Arctic ocean as sea ice retreats”, The Independent, 13 December, 2011, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/vast-methane-plumes-seen-in-arctic-ocean-as-sea-ice-retreats-6276278.html

The Siberian Times, “Arctic methane gas emission ‘significantly increased since 2014’ – major new research”, 4th October 2016, http://siberiantimes.com/ecology/others/news/n0760-arctic-methane-gas-emission-significantly-increased-since-2014-major-new-research/

Herrero, M., Havlík, P., Valin, H., Notenbaert, A., Rufino, M.C., Thornton, P.K., Blümmel, M., Weiss, F., Grace, D., and Obersteiner, M. “Biomass Use, Production, Feed Efficiencies, and Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Global Livestock Systems”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, no. 52 (2013): 20888-20893, http://www.pnas.org/content/110/52/20888

Sejian, V., Gaughan, J., Baumgard, L., and Prasad, C., Climate Change Impact on Livestock: Adaptation and Mitigation, Springer, 2015, Chapter 1, p. 2, http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9788132222644

Carbon Visuals, Actual volume of one metric ton of carbon dioxide gas, Flickr

Gerber, P.J., Steinfeld, H., Henderson, B., Mottet, A., Opio, C., Dijkman, J., Falcucci, A. & Tempio, G., 2013, “Tackling climate change through livestock – A global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities”, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, Table 5, p. 24, Fig. 4, p. 17

Harper, L.A., Denmead, O.T., Freney, J.R., and Byers, F.M., Journal of Animal Science, June, 1999, “Direct measurements of methane emissions from grazing and feedlot cattle”, J ANIM SCI, 1999, 77:1392-1401, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10375217; https://academic.oup.com/jas/article/77/6/1392/4625488; http://www.journalofanimalscience.org/content/77/6/1392.full.pdf

Eshel, G., “Grass-fed beef packs a punch to environment”, Reuters Environment Forum, 8 Apr 2010, http://blogs.reuters.com/environment/2010/04/08/grass-fed-beef-packs-a-punch-to-environment/

UNFAO email correspondence of 21st April, 2nd May and 27th June 2017

Springmann, M., Godfray, H.C.J., Rayner, M., Scarborough, P., “Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change”, PNAS 2016 113 (15) 4146-4151; published ahead of print March 21, 2016, doi:10.1073/pnas.1523119113, (print edition 12 Apr 2016), http://www.pnas.org/content/113/15/4146.full and http://www.pnas.org/content/113/15/4146.full.pdf

Pan A, Sun Q, Bernstein AM, Schulze MB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB. Red Meat Consumption and MortalityResults From 2 Prospective Cohort Studies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):555-563. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.2287, http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/1134845

Bakalar, N., “Risks: More Red Meat, More Mortality”, The New York Times, 12 March, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/13/health/research/red-meat-linked-to-cancer-and-heart-disease.html?_r=1&scp=2&sq=red%20meat%20harvard&st=cse#

Pan A, Sun Q, Bernstein AM, Schulze MB, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB, Red meat consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: 3 cohorts of US adults and an updated meta-analysis, Am J Clin Nutr

ajcn.018978 , http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/early/2011/08/10/ajcn.111.018978.abstract

Shaw, J., A diabetes link to meat, Harvard Magazine, Jan-Feb 2012, http://www.harvardmagazine.com/2012/01/a-diabetes-link-to-meat

Dwyer, M., Red meat linked to increased risk of type 2 diabetes, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 10 Aug 2011, https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/press-releases/red-meat-type-2-diabetes/

World Cancer Research Fund, “Diet, nutrition, physical activity and Breast Cancer Survivors- 2014“, http://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Breast-Cancer-Survivors-2014-Report.pdf

World Health Organization, “Breast cancer: prevention and control”, http://www.who.int/cancer/detection/breastcancer/en/index2.html

World Cancer Research Fund – Recommendations, http://www.dietandcancerreport.org/cancer_prevention_recommendations/index.php

Harvard University, T.H. Chan School of Public Health, “WHO report says eating processed meat is carcinogenic: Understanding the findings”, undated, https://www.hsph.harvard.ed/nutritionsource/2015/11/03/report-says-eating-processed-meat-is-carcinogenic-understanding-the-findings/

Kennedy P. M., Charmley E. (2012) “Methane yields from Brahman cattle fed tropical grasses and legumes”, Animal Production Science 52, 225–239, Submitted: 10 June 2011, Accepted: 7 December 2011, Published: 15 March 2012, http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/AN11103

CSIRO Media Release, “Research sheds new light on methane emissions from the northern beef herd”, 27th May 2011, https://csiropedia.csiro.au/research-sheds-new-light-on-methane-emissions-from-the-northern-beef-herd/

Images

Alexey Suloev, “Beautiful view of icebergs and whale in Antarctica”, Shutterstock, Photo ID: 543672994

NSIDC Map by Philippe Rekacewicz, visionscarto.net. (Used with permission)

Carbon Visuals, Actual volume of one metric ton of carbon dioxide gas, Flickr, Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

Volume Calculations

1 gigaton = 1 billion tonnes

1 tonne of H2O = 1 cubic metre

1 tonne of CO2 = 534.8 cubic metres

1 gigaton of H2O = 1,000,000,000 cubic metres

1 gigaton of CO2 = 534,800,000,000 cubic metres

36 gigatons of H2O = 36,000,000,000 cubic metres

36 gigatons of CO2 = 19,252,800,000,000 cubic metres

1 Olympic-sized pool = 2,500 cubic metres

36 gigatons of H20 = 14,400,000 Olympic-sized pools

36 gigatons of CO2 = 7,701,120,000 Olympic-sized pools

Notes:

Updates

The item “Animal suffering, human health, and more on climate change” was added on 15th March 2018, subsequent to the initial release.

New paragraph and reference added in relation to managed grazing on 18th March 2018.